Many people have requested that I do a blog post on genetics. Genetics--even if we limit it to the basic color genes of rabbits--is a rather large topic, which really won't fit into a single blog entry. So, I'm going to break it down into sections. If you think that the blogging method is too slow for you, go check out my

website on rabbit genetics.

This post is going to just go over the basics of how genes work. Nothing specifically applies to rabbits. In fact, the following applies to genetics in just about everything!

There are genes which control just about every possible trait. Many traits are controlled by several genes, which, in combination make the end result. For each trait, a gene is contributed by

each of the parents (except for sex-linked traits, but they're a non-issue with rabbits, so far). Whichever gene of the resulting pair is

most dominant determines what version of the trait the offspring will have.

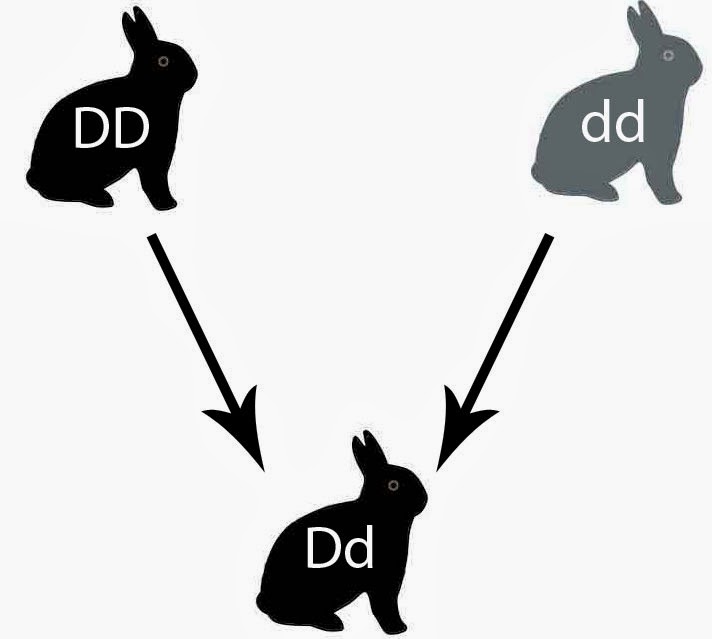

Let's say that we have a pair of rabbits, one of which shows the dominant version of the trait, D, and the other which shows the

recessive version of the trait, d. (In genetic notation, genes which are in the same series are represented by the same letter, with the capital letter designating dominance, and the lower case letter representing recessive). Every rabbit has two genes for every trait. For the sake of simplicity, let's say that both of these rabbits have two identical genes (called

homozygous ["homo" means same, "zygo" means pair]), meaning that no matter what, they will give the gene for the trait that they show.

The resulting offspring will have one gene for the dominant version and one gene for the recessive version (called

heterozygous ["hetero" means different]). In most cases, this results in a rabbit which shows only the dominant version of the trait. However, because the rabbit has the gene for the recessive version--in other words, "carries" for it--it may be able to produce kits which show the recessive version of the trait.

When a rabbit is heterozygous, it could pass on

either gene. Essentially, it's a coin flip which gene a kit will get from each parent. There's a way to predict the outcome on paper, using a tool called a Punnet Square, which looks like this:

To set up a Punnet Square, you put each of the parents' genes on the outside of the box. One parents' genes get to be the labels for the top, and the other's make up the side. In this case, both parents are Dd (heterozygous), but they could just as easily be any combination of that, or DD, or dd. Inside the squares, you combine the two labels associated with that square. So, the first box is under the blue D, and next to the red D, so it gets to be DD. In the second box, it is under the blue d, and next to the red D, so it would be dD. However, when writing genetics, you always write the most dominant gene first, so the letters would get switched around to be Dd. Keep filling out the squares until it's complete.

Once a Punnet Square is filled out, it shows you all possible combinations of those genes. On top of that, it tells you how

likely each combination is. The above Punnet has four squares. In one of the squares, the combination is DD, meaning that about 1 in 4 kits from that crossing should be DD (homozygous dominant). Two of the squares show Dd (the color at this point doesn't matter), which means that 2 in 4--or half--of the kits would be expected to be Dd (heterozygous). The remaining 1 square is dd, so you'd expect 1 in 4 kits to be dd (homozygous recessive).

DD, Dd, and dd are examples of

genotypes--that is, genetic codes. However, DD and Dd rabbits will look the same, because both will express the dominant version of the trait. That makes them the same

phenotype (physical expression). If you look at the Punnet Square, you'll see that 3 in 4 squares have a D in them, meaning that they will show the dominant phenotype. (You can further break that down to say you'd expect 2 out of 3 dominant-versions to be heterozygous). Only 1 in 4 of all the offspring will show the recessive phenotype, because recessive

only shows when there is

no dominant gene to override it. That also means that any rabbit which shows a recessive phenotype

must be homozygous for that gene, which in turn means that they

must contribute that gene to

every one of their offspring.

However, the 1 in 4, 2 in 3, etc. are only averages over an extended period of time. It's a coin flip

every time, and the coin doesn't care what the last flip came up as. To illustrate this point, I'll cite the fact that you

should expect about half of every litter to be male, and the other half to be female. But, it's really not all that uncommon to end up with a whole litter (even a whole litter of 8 or 9 kits) be entirely one sex.

That's why you can't say, definitively, that a rabbit with a dominant trait

doesn't carry for the recessive trait. Most breeders will feel fairly confident if that rabbit has produced at least 16 kits, from breeding to a rabbit that

is the recessive trait, without a single kit showing the recessive trait. However, if it ever produces even a single kit with the recessive trait, it absolutely

must carry for it. Also, if either of its parents show the recessive trait, it

must carry for it.

In sum:

- The trait a rabbit shows is its most dominant trait; the other gene must either be the same (homozygous) or recessive to it (heterozygous)

- A rabbit which shows the recessive trait must be homozygous recessive

- A homozygous rabbit always throws that gene

- A rabbit with a recessive-trait parent must carry for the recessive gene

- A rabbit which has thrown a kit with the recessive trait must carry for the recessive gene (applies to both parents)

- If a rabbit that shows a dominant trait comes from unknown or same-trait parentage, and has not been bred, there is no way to know if it carries a recessive or not until it's been test-bred

- Punnett Squares show all possible outcomes

- Punnett Squares can estimate the likelihood of a particular genotype or phenotype, but only show long-term averages